Reclaiming the Forest: Jharkhand’s Path to True Tribal Self-Governance Through Legal Empowerment and Constitutional Justice

Introduction

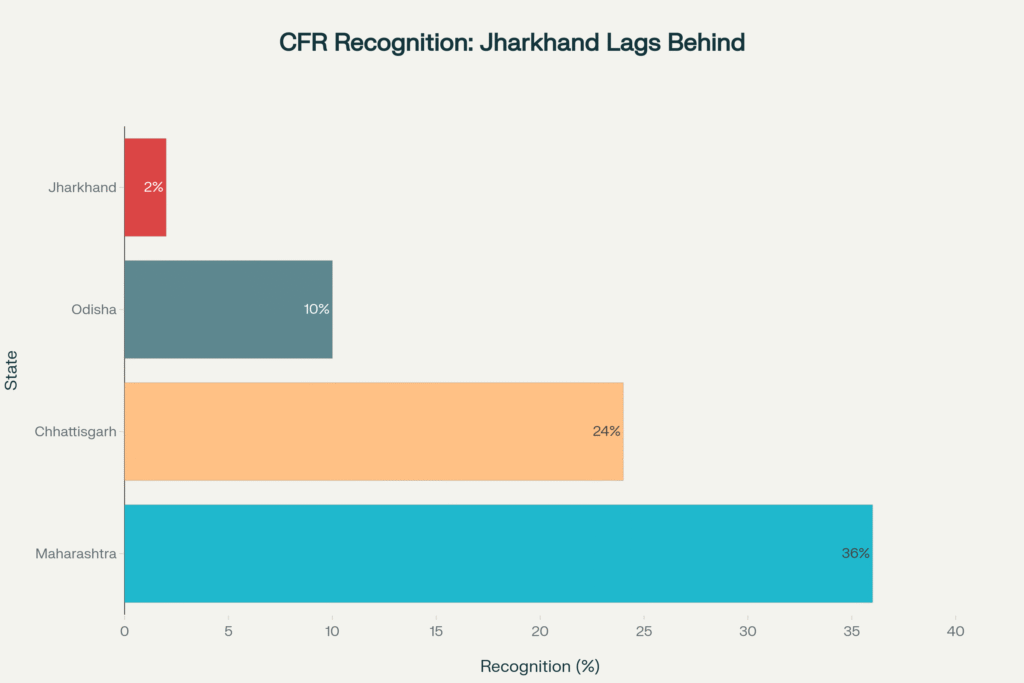

In the heart of India lies Jharkhand, a state whose very name means “Land of the Forest” yet it has become a stark symbol of broken promises to its tribal communities. While possessing one of the world’s most progressive legal frameworks for indigenous governance, Jharkhand has achieved the dubious distinction of recognizing less than 2% of eligible community forests, compared to Maharashtra’s impressive 36%. This devastating gap between constitutional promise and ground reality represents not just policy failure, but a betrayal of 8.3 million tribal people whose ancestors have stewarded these forests for millennia.

Jharkhand’s tribal-dominated regions depend on dense forests and common land for their livelihood. The 73rd Amendment enshrines the Gram Sabha (village assembly) as the foundational body of rural self-governance. Scheduled Areas (like much of Jharkhand) enjoy extra protection: Article 244(1) and the Fifth Schedule require Parliament’s oversight of laws there, while Part IX of the Constitution (Articles 243A– 243O) and the Eleventh Schedule (listing local subjects such as social forestry, minor forest produce, minor irrigation, minor minerals, and water management) empower Gram Sabhas through the state. In short, Gram Sabhas are constitutionally vested with rights over land, water, forests, and local resources.

Statutory law Reinforces This

The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) explicitly extends Part IX to tribal areas. PESA entrusts Gram Sabhas with managing community resources, regulating “minor minerals” (sand, gravel, etc.), banning intoxicants, and vetoing land transfers or mining in their villages. PESA mandates that Gram Sabha consent is required before any project affecting tribal land or resources. The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (FRA) further empowers Gram Sabhas: Section 5 makes the Gram Sabha the primary authority to manage and protect forests, and Section 3(1)(i) grants them community forest rights (CFR) over customary commons.

Even Jharkhand’s state law (the Jharkhand Panchayati Raj Act, 2001) incorporates the PESA principles. Jharkhand High Court time and again has reiterated that in Scheduled Areas Gram Sabhas are empowered “to maintain natural resources, pertaining to the village, which includes soil, water and forest, as per existing tradition”.

Thus, both national and state laws envisage Gram Sabha sovereignty in tribal villages, covering planning, resource use, and cultural autonomy .

Judicial Mandates on Gram Sabha Authority

Indian courts have reinforced these foundations. In Orissa Mining Corporation Ltd. v. Union of India (2013) 6 SCC 476 (“Vedanta” case), the Supreme Court held that “the gram sabha has both a duty and a power over forest management” under FRA section 5, including protecting “their habitat from any form of destructive practices” . The Court expressly read FRA and PESA together, noting that Section 4(d) of PESA “confers powers on the Gram Sabha to determine the nature and extent of individual or community rights,” and that Gram Sabhas have an “obligation to safeguard and preserve the traditions and customs…of the STs and other forest dwellers” .

In Samatha v. State of A.P., AIR 1997 SC 3297, the Court invalidated mining leases on tribal land, holding that “government, tribal, and forest lands in the Scheduled Areas cannot be leased to non-tribal persons” and any such transfer is void under the Fifth Schedule. (Samatha thus affirmed that Scheduled Area lands are held for tribal welfare, precluding non-tribal exploitation).

While Jharkhand-specific case law is nascent, a 2024 Jharkhand High Court decision (“Gram Sabha v. State of Jharkhand”) similarly reaffirmed Gram Sabha consent as mandatory for any forest diversion in Scheduled Areas (reflecting the Vedanta principle that tribal consent is integral to project approvals). These judgments collectively underscore that any land-use or extractive project in Jharkhand’s Fifth Schedule areas must secure Gram Sabha consent and protect customary rights .

The Stark Reality: Rights on Paper, Powerlessness in Practice

Despite this robust legal framework and favorable jurisprudence, Jharkhand’s tribal forests remain largely unempowered in practice. For instance, as of 2025 only a tiny fraction of potential community forests have been legally recognized. Studies show Jharkhand has granted less than 2% of its eligible Community Forest Resource (CFR) claims – one of the lowest rates nationally. (By contrast, Maharashtra has recognized CFRs over ~36% of its potential area, Chhattisgarh ~24% and Odisha ~10%.) This gap persists due to multiple factors:

– Lacking Awareness: Many forest dwellers do not know their rights under FRA/PESA. Officials rarely publicize eligibility or procedures, and Gram Sabhas lack legal aid.

– Bypass by Forest Bureaucracy: Forest departments habitually treat forest land as their sole domain. They often ignore Gram Sabha resolutions or push through clearances (sometimes citing conservation), in defiance of FRA mandates. Historic patterns of “forest as state property” persist despite the law.

– Weak Institutions and Infrastructure: Jharkhand’s Gram Panchayat infrastructure is poor. Only 37% of Common Service Centres (Pragya Kendras) actually operate from the mandated Gram Panchayat offices, and many lack electricity or internet. Without basic Panchayat Bhawans or digital connectivity, mobilizing and recording Gram Sabha meetings is difficult. Similarly, there are too few Community Resource Persons (CRPs) or legal aid clinics to guide villagers in making claims.

– Under-used 5th Schedule Funds and Concessions: The state has not effectively leveraged special funds or discretionary quotas earmarked for tribal areas. For example, no comprehensive Jharkhand- specific FRA rules have been issued (unlike some states), and PESA rules were drafted only recently (22 years after enactment). Tribal communities thus miss out on empowered planning.

– Stalled Land Rights Adjudication: Individual Forest Rights (IFR) claims by Scheduled Tribe households have also stagnated. FRA data (GOI) indicates recognized IFR claims in Jharkhand are well below targets, partly due to apprehensions in revenue offices. Nor are women’s and PVTG (Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group) applications receiving priority, despite special provisions in FRA.

These gaps mean Jharkhand’s Gram Sabhas, though empowered on paper, remain marginalized in actual governance of forests. As a study observes, denial of CFRs tends to “lead to degradation of forests” as department-led logging proceeds unchecked . In sum, Jharkhand has the laws but not the mechanisms: its tribal commons remain under forestry department control, with Gram Sabhas playing little real role.

Learning from Success: Proof That Transformation Is Possible

Maharashtra – Community Mobilization & Benefit-Sharing:

Maharashtra leads the country in CFR recognition. The 2009 case of Mendha-Lekha (Gadchiroli) became a model: the Gram Sabha obtained CFR over ~1,800 ha, reforested bamboo groves, and instituted collective bamboo harvesting for livelihood . Local committees “view villagers as rights-holders rather than beneficiaries,” investing forest revenues in schools and infrastructure.

This bottom-up approach shows that Gram Sabha institutions, not outside NGOs, can drive sustainable forest management. Maharashtra’s tribal Gram Sabhas also pioneered Community Forest Rights Committees and Village Forest Development Committees under PESA, where trained members implement Joint Forest Management-type activities on their terms.

Odisha – Digital Mapping & Gram Sabha “Referendums”:

Odisha has actively recognized CFRs in recent years. The state in 2021 granted CFR rights to 4,098 of 6,068 claimant villages , often over large contiguous forests. Innovative NGOs like PRADAN have used digital mapping tools to document claims: e.g., PRADAN’s Rayagada project maps village boundaries via GPS to create formal land records, significantly speeding FRA claim approvals.

In Kandhamal, district collectors actually convened Gram Sabhas for mining proposals: after community referendums in 2013, the Dongria Kondh villagers of Niyamgiri exercised their CFRs to unanimously reject a bauxite mine. These Odisha examples illustrate how technology and political will can make Gram Sabha rights visible and enforceable.

Chhattisgarh – Rapid CFR Recognition:

Chhattisgarh, despite lacking formal PESA rules, embraced CFRR (Community Forest Resource Rights). After the first CFRR grant in 2019 ( Jabarra village), a statewide drive won 3,782 CFRR titles for 3,903 villages by 2022 – nearly all applicants. This blitz, aided by UNDP support and local NGOs, generated a cascade effect: acceptance in one village spurred neighboring communities to file claims. Notably, Chhattisgarh’s elected tribal leadership publicly backed Gram Sabha claims, signaling political commitment. This shows that even without perfect laws, concentrated administrative effort can unlock Gram Sabha authority at scale.

Community Mapping and Planning:

Across these states, a common practice is participatory mapping by the Gram Sabha. Villagers draw their traditional boundaries (with elders’ input), use GPS devices, and invite forest/revenue officers to verify the area . Such maps, endorsed by the entire village assembly, become part of FRA claims or village development plans. For example, Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh tribes rope in local colleges or NGOs to digitize maps, ensuring claims are accepted smoothly . Jharkhand’s villages can similarly map rivers, groves and sacred sites, strengthening their legal standing.

Grassroots Training (Community Resource Persons):

In Odisha and Chhattisgarh, trained youth (CRPs) move village-to-village raising FRA/PESA awareness and helping file claims. Some states provide stipends for CRPs to act as paralegals in Gram Sabhas. Jharkhand’s tribal NGOs (like NSVK, Vasundhara) have begun CRP trainings, which can be scaled statewide. “Gram Sabha legal clinics” supported by law schools (as piloted in Karnataka or Telangana) could also provide mobile legal aid in remote blocks.

These examples offer a template: empowered Gram Sabhas, backed by clear maps and allied support, can effectively manage forests and resources. Jharkhand can adopt these proven practices e.g. statewide FRA mapping drive, Gram Sabha-led forest committees, and Gram Sabha veto over mining – to realize its latent legal commitments.

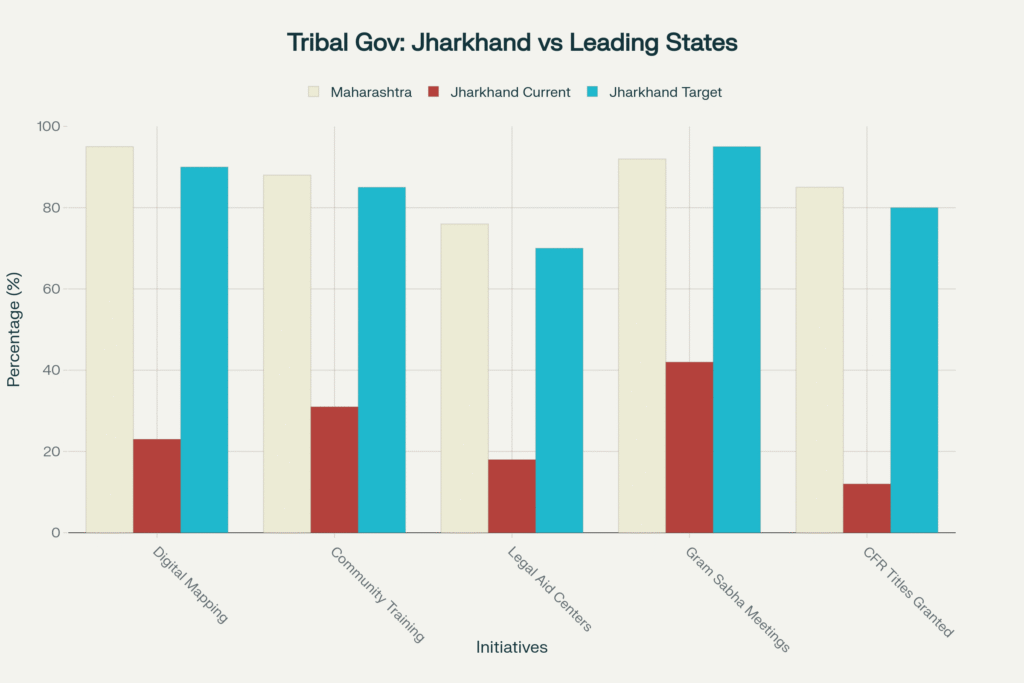

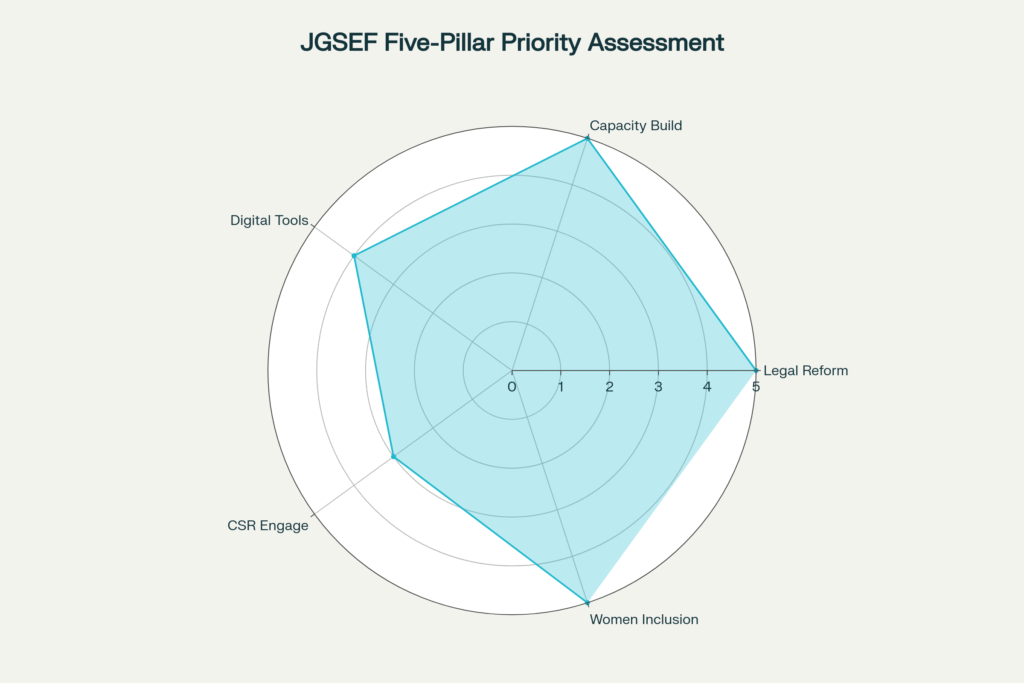

Jharkhand Gram Sabha Empowerment Framework : A blueprint for transformation

Building on the above, we propose a Jharkhand Gram Sabha Empowerment Framework ( JGSEF) comprising five interlocking policy pillars. These pillars outline the concrete steps needed to make Gram Sabhas self-governing units for forests and tribal welfare.

1. Legal & Administrative Measures

• Enact and Enforce State Rules: Finalize Jharkhand-specific FRA and PESA rules. The FRA (2006) leaves some rule-making to states (especially in designating authorities); Jharkhand must issue clear rules for claim processing (as in Odisha) and ensure PESA’s clause (4) on monitoring intoxicants and minor minerals is codified. Jharkhand can model its rules on best-practice states, mandating Gram Sabha permission for all local mining or forest diversions.

• Strengthen State Laws: Amend the Jharkhand Panchayat Act (2001) to explicitly integrate FRA duties. For instance, make FRA claim sanction one of the Gram Sabha’s statutory functions, and require Gram Sabha endorsements for forest block leases or auction of minor forest produce (as initially envisioned under PESA §4(h)–(j)). This aligns the state law with jurisprudence like Vedanta and Samatha.

• Gram Sabha Development Plans: Institute a mandatory Gram Sabha Plan for each village (as suggested under 14th Finance Commission guidelines), to be approved by the Gram Sabha. In Scheduled Areas these plans must prioritize CFR management, customary irrigation, community funds (per FRA §3(1)(h)), and local craftsmanship. The Annual Plan process (under JICA-funded JHARSAKTI or district planning) should begin with Gram Sabha resolution in tribal villages.

• District Forest Rights Cells: Operationalize dedicated FRA cells (already sanctioned by MOTA) in all districts. These multi-departmental cells would monitor claim pendency and Gram Sabha resolutions. For example, the FRU (Forest Rights Unit) in Orissa proved effective. Jharkhand can set up similar cells in each division, headed by a Collector or high-level officer, to coordinate between tribal, forest and revenue departments.

• Festivals of Decentralization: Institutionalize annual “Gram Sabha Melas” in tribal districts on Birsa Munda Jayanti (Nov 15, a Janjatiya Gaurav Diwas) to review implementation and renew commitments. This mirrors initiatives in Chhattisgarh (where District Collectors hold yearly Gram Sabha meets). Public dashboards (online and at District offices) should report FRA and PESA compliance rates.

2. Capacity Building & Legal Clinics

• Gram Sabha Legal Aid Clinics: Establish Gram Sabha Resource Centers (one per block) staffed by paralegal or legal-aid teams. These teams (drawing on Village Legal Volunteers under the State Legal Services Authority) will attend Gram Sabha meetings, help draft resolutions, and explain legal rights in local languages. Mandate that Gram Panchayat Bhawans be the venue for legal camps. As Jharkhand’s Human Rights Commission has noted, rural legal literacy is low – clinics help bridge this gap.

• Training of Panchayat and Forest Staff: Conduct dedicated training modules for Block Development Officers, Forest Range Officers, and Forest Rights Committees about Gram Sabha rights. Workshops can clarify that FRA requires Gram Sabha certification of claims and that conservation programs (like CAMPA) cannot override forest rights. Include civil society monitors in training so they become accountability partners.

• Community Resource Persons (CRPs): Scale up the CRP model. Select youths (especially women and Adivasi) from each Gram Sabha and train them in claim procedures, demarcation, and community mapping. Provide small honoraria to incentivize continued work. These CRPs will be the first point of contact for villagers and will ensure claims are filed correctly. Partnerships with law colleges or NGOs can formalize CRP training curricula.

• Local Gram Sabha Funds: Direct a portion of CAMPA (Compensatory Afforestation) funds and 14th FC untied grants to Gram Sabha Development Funds in tribal villages. Gram Sabhas can use these funds for legally authorized purposes (e.g. watershed works, school repair, minor irrigation bunds) under PESA §4 and FRA §3(i). The Gram Sabha itself should approve budgets and all expenditures, monitored through social audits.

3. Digital Tools for Transparency

• Geo-spatial Mapping Portals: Deploy a web-GIS portal (or mobile app) showing village boundaries, FRA claims status, and natural resources. Villagers and officials can use this portal to see which village forests are legally recognized as CFR and which remain claimed. The portal should integrate Revenue and Forest Department maps. For example, Odisha’s FRA cell uses GIS to speed up approvals; Jharkhand can partner with ISRO’s BBMP or NIC’s Bhuvan platform for mapping.

• Digitize Claim Records: Launch an online tracking system for FRA claims (building on the existing “FRA Portal” but customized for Jharkhand). Under this system, Gram Sabha resolutions and approved claim lists are published online. Public dashboards would track outcomes of Gram Sabha resolutions (e.g. number of CFR titles granted). This transparency pressures officials to act.

• E-Gram Sabha (Video Conferencing): Equip Gram Panchayat Bhawans (where available) with video conferencing (VC) links to Block and District HQ. During FRA hearings, if a department official is absent, the Gram Sabha can meet via VC with the collector or revenue director to push grievances (as in the Rajasthan e-Panchayat model). Similarly, Gram Sabha orders (under FRA) could be immediately faxed/e-mailed to district authorities via a secured ICT network.

• SMS Alerts and Mobile Apps: Register tribal households’ mobile numbers to receive SMS alerts on FRA claim milestones (acknowledgment of claim, verification date, sanctioning of title). A simple app or SMS-based service can remind elected Gram Sabhas of scheduled meetings, revenue hearings, or mining project proposals affecting their village. (Digital outreach can leverage the BharatNet infrastructure to connect Village Knowledge Centers.)

4. CSR Engagement

• Forest Rights Awareness by Industry: Mandate that companies operating in or near tribal areas (mining, power, steel) must allocate CSR funds to strengthen Gram Sabhas, as part of their ‘Social Impact Assessment’ plans. For example, local steel companies or coal blocks can sponsor legal literacy camps and mapping drives. Companies already commit to Tribal welfare in EIA clearances – channeling that investment into Gram Sabha capacity building (rather than unrelated projects) would align CSR with statutory Gram Sabha rights.

• Village Development Partnerships: Encourage CSR-funded “Village Resource Trusts” where a Gram Sabha oversees development budgets. For instance, a mining company could endow a corpus whose interest supports community veterinary services or school scholarships in Gram Sabhas that lost some forest cover. The Gram Sabha (not the Panchayat) should manage such funds and set priorities. This makes corporate dollars answerable to the villagers.

• Technical Grants for Mapping and Management: Corporations can partner with technical institutes to provide GPS units, training, or drones for mapping community lands. Many companies today fund GIS/remote-sensing projects for forest monitoring. CSR projects can be tapped to train Gram Sabha members in these technologies. (E.g. a CSR project in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli funded digital forest mapping in tribal villages.)

5. Women’s Inclusion

• Affirmative Gram Sabha Roles for Women: Ensure that at least 50% of Gram Sabha and FRA- related committee members are women. While the 73rd Amendment requires female reservation in Gram Panchayats, the FRA Rules also emphasize Gram Sabhas must be inclusive. Jharkhand should require that every CFR claim or forest management plan be approved by a Gram Sabha with a woman member quorum, e.g. mandating at least 1/3 of voting members be women. This could be formalized in FRA implementation guidelines (echoing models from Kerala’s forestry boards).

• Support for Single Women Claimants: Many tribal women (widows or separated) are forest dwellers. Under FRA §3(1)(m), single-women-headed households have priority for individual rights. Jharkhand authorities should conduct special Gram Sabhas to help such women file claims. Legal clinics should proactively identify single women and educate them. Successful models in other states, like Bihar, have offered preference to women in claims; Jharkhand could issue state guidelines to replicate this.

• Women’s Forest Committees: Promote the formation of Mahila Gram Sabha Sabhas or women-led committees at the hamlet level. These committees can focus on protection of NTFPs (mushrooms, fruits, fibers) and medicinal plants – resources crucial for women’s livelihoods. Funds (FRA §3(1)(m)) can be reserved to train women in value-added NTFP processing (e.g. tending kendu leaf plants or honey). By involving women centrally, Gram Sabha decisions will better reflect the entire community’s needs.

• Link to Tribal Self-Help Groups (SHGs): Many women in Jharkhand are organized in SHGs under DAY-NRLM. Linking SHGs to Gram Sabhas – for instance, by inviting SHG Federations to nominate members to forest committees – can ensure women’s voices in forest governance. SHG Federations can also be tasked (via CSR or state support) to run timber/sapling nurseries on CFR lands, giving women-controlled enterprises on community forests.

Conclusion

Jharkhand stands at a crossroads. The legal framework – from Articles 243A and 244 to PESA and FRA – unequivocally vests forest and tribal governance in the Gram Sabha’s hands. Supreme Court rulings like Vedanta and Samatha further mandate that development cannot override tribal self-rule. Yet currently <2% of Jharkhand’s potential community forests are recognized , and most villages remain unaware of their rights.

The comprehensive Jharkhand Gram Sabha Empowerment Framework we propose – spanning law reform, grassroots capacity, digital tools, CSR partnerships and women’s leadership – offers a scalable path forward. By legally reinforcing Gram Sabha consent, building village-level capacity (through CRPs and legal clinics), increasing transparency with mapping apps, and ensuring women’s full participation, Jharkhand can transform its relationship with its forests. Time is of the essence: unchecked mining and deforestation threaten tribal livelihoods and biodiversity alike. In the words of activists, “Instead of state-sanctioned felling, FRA enables a statutory process of decentralised forest management by the gram sabha” .

To honor its founding promises, Jharkhand’s policymakers must now move beyond rhetoric. Implementing Gram Sabha-centric governance is not only constitutionally required, it is the most sustainable path to empower adivasi communities and protect Jharkhand’s forests. This White Paper thus calls for urgent, coordinated action: adopt the JGSEF pillars, enforce Gram Sabha oversight, and make Jharkhand a national model for tribal self-governance and forest justice.

Sources: Constitutional provisions (Articles 243A, 244, Eleventh Schedule); PESA 1996; FRA 2006; Jharkhand Panchayat Raj Act 2001 . Key judgments include Orissa Mining Corpn. v. Union of India, (2013) 6 SCC 476 ; Samatha v. State of A.P., AIR 1997 SC 3297 . Implementation data and analysis from various research sources, and field reports.